Hey SIX followers!

Hope you’re doing well this week.

This week, we’re going to start a basic theory series, hopefully, at the end of this series, we will understand how the Nashville Number System. In order to learn about the Number System, you are assumed to have a basic knowledge of the mechanics of music theory. If you already know this stuff, just bear with me this week, so we can have a common foundation from which to build. So let’s start from the beginning, shall we?

The Staff

In order know about theory, we need to know about the way music has been written and thought about for about the last 400 years. Music is written on a staff of five lines and four spaces, usually with one of three clefs. Since I am a guitar player, I will speak about the “G” Clef, or “Treble Clef.”

The G Clef is so called because the circular flourish at the end of the Clef Symbol surrounds the second line, which is where the note “G” is located. It looks like this:

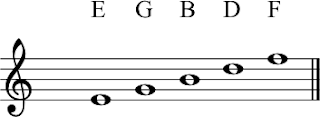

If G is on the second line, the notes fall on the lines of the staff like this:

Usually people use some kind of mnemonic device to remember these when they are first using them, like “Every Good Boy Does Fine” or “Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge.”

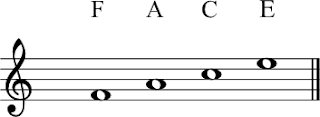

If those are the lines on the treble clef, the spaces look like this:

It’s pretty easy to remember these notes, as they spell “FACE” from bottom to top.

These are all the natural note names of all the positions on the staff. Usually, though, composers need to extend the staff to positions outside the range of the staff. For this, they use “Ledger Lines.”

Here are some examples of ledger lines that are being used to place notes beyond the range of the staff:

Accidentals

Also, if you know much about music, you know that there are not only seven notes in any octave, there are twelve. The notes shown above represent “natural” notes, that is, notes that have no “accidentals” or sharps and flats in front of them. A flat, which looks vaguely like a lower case “b,” lowers a note by one half step, while a sharp, which looks like a “pound” sign ( #) raises a note one half step.

The Major Scale

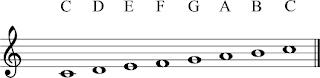

Ok. Composers noticed that when you played the noted of the staff from low to high, it sounded a certain way. This is an arrangement called a “scale” and for about 400 years, this has been the basic building block of all western music. The scale used most in western music is called the major scale, and it is always arranged in a certain way. Here is a major scale built off of C:

When you play this scale, you should recognize the familiar ” Do Re Mi Fa Sol La Ti Do” sound. This scale sounds that way because of the arrangement of the whole and half steps between each note. When we examine the arrangement of the whole and half steps between each degree of the scale, here is what we get:

So: whole step between C and D, whole step between D and E, half step between E and F, whole step between F and G, whole step between G and A, whole step between A and B, and half step between B and C.

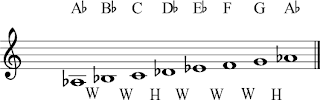

With this formula, we can build a major scale off of any note, like A-flat:

…and I think that may be enough for this week, Next time, we’ll talk about intervals, and triads, most likely.

This Week:

Still working on the production project, got a cool new song in the works….

Have fun!

Write Something, will ya?